Deltarune Refuses to Leave People with Autism Behind—And We Should Take Notes

Posted: 17 Feb 2023“The tragedy is not that we’re here, but that your world has no place for us to be” Jim Sinclair passionately declares in his essay “Don’t Mourn For Us”.

From anti-vaccine activists purporting autism as a malignant side effect from boosters–which remains disproven–to active organizations like Autism Speaks seeking to vilify and eliminate autism in children instead of spreading advocacy for better living, being autistic unfortunately remains something the world wants to eradicate instead of embrace, even though these behaviors are beyond one’s control.

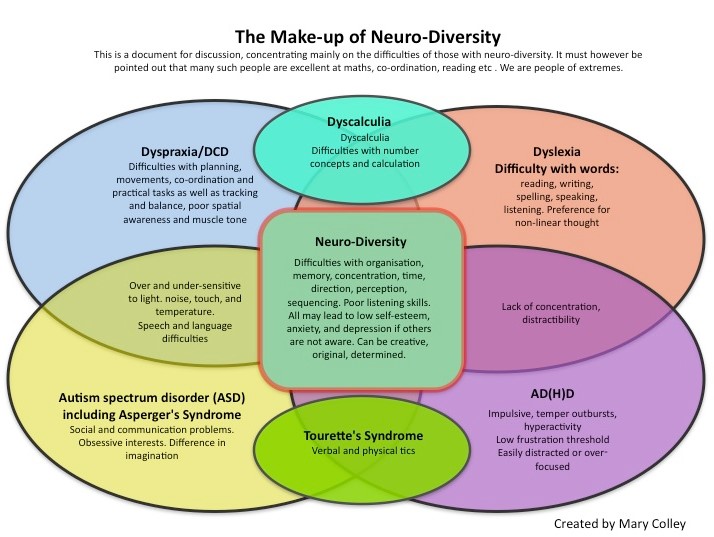

And “nobody chooses who they are”, Deltarune reminds you after creating a character they immediately dismiss–but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Autism is not a looming monster waiting to strike; it has existed and continues to exist all around us in a multitude of ways. In fact, as of 2022, the CDC states that 1 out of 100 children are diagnosed with autism each year–that is not a low number, a statistic that doesn’t even take into account the history of misdiagnoses and the lack of diagnoses in specific populations: women, BIPOC, LGBT people, and people in poverty. More than likely, you have met many people with autism and have not even known it, because autism is not a monolithic diagnosis with archetypal identifiers. It is replete with diversity, which fortifies Sinclair’s argument that to be autistic is to just be another type of person in this compendium of characters we call humanity.

Toby Fox assembles his own compendium of autistic coded characters in Deltarune, a cast that has certainly won the hearts of the online neurodivergent community.

There is Kris, the main character you play as that is sensitive to physical contact and mute; Susie, the tough monster that is fiercely independent yet struggles with problem-solving; Ralsei, the prince of darkness that fixates on niche subjects; and Lancer, the imaginative, bad-guy-turned-good-guy after finding friendship. All of these characteristics are classified as autistic behaviors, but what makes these characters stand out compared to other autistic video game characters like Symmetra from Overwatch and Wattson from Apex Legends, is that Fox places these characters in settings where other autistic children have been: left to fend for themselves.

As it is widely known that special education programs in public schools are underfunded and underdeveloped in the United States, children with autism are often left to fend for themselves, and may develop bad habits as a result. Susie demonstrates a self-destructive hyper-independence –because of a history of being unable to rely on anyone–unshakably set in her disruptive ways with no friends. Alphys, her teacher, does not bother to reprimand her for her chronic lateness and rude behavior toward her other classmates, but instead cowers before her. Kris is also chronically late, and when they enter class, Alphys is similarly dismissive of it, simply saying, “we didn’t think you were going to be here today”. There is a demonstrable lack of care for both of these students that they sadly have grown accustomed to–after all, why should they care when their adult role model outside of family doesn’t, and sends them out of the classroom at their first chance?

This school–their world–does not seek to know them, so it makes sense that when they fall into the Dark World, Susie and Kris are apprehensive of Ralsei, who has been waiting for them to be heroes with him. Together, they are bound to save the world, whereas they are lost by themselves–and this mirrors the real world.

Statistically, children with autism are less likely to participate in community activities, even though community participation positively impacts physiological, emotional, social, and mental growth.

Each character experiences growth when they work together. Susie develops empathy by finding a genuine friend in Lancer; Kris, a comparably indifferent character, finds comfort in Ralsei’s unfiltered joy and optimism; and Susie helps Ralsei realize there is no “right” or “one” way to be a hero, despite what he has been told he and his destined hero friends are supposed to act—the latter being reminiscent of Sinclair’s reminder that autistic people are simply exhibiting another type of living that is conventionally different. Susie, who has a hard time solving puzzles AND reaching out for help, reaches out to Kris and Ralsei for help, and she gradually becomes better at solving them herself. As a whole, the gang approaches their journey nonviolently, complimenting and listening to their enemies–even though the autistic community has a negative reputation for being “difficult” and even “violent” when they don’t act in line with unspoken social rules.

With such a considerable percentage of children being diagnosed with autism, how is it that we have such a long way to go when it comes to making them feel safe and accepted in this world?

That’s where games step in.

To play games is to enter a world where your brain is engaged on all echelons–physically, emotionally, mentally–and you are entirely in control. You can pause and return to it, and dive right back in when you’re ready. You also develop motor skills, problem-solving skills, and most importantly, the opportunity to practice social skills online without the pressures of in-person social conventions. These factors in video games may explain why 41.4% of neurodivergent people are more likely to spend their free time playing video games compared to 18% of the neurotypical population.

In short, games are the perfect social playroom for neurodivergent people.

Mental health organizations such as GametoGrow and AbleGamers invite all people with autism to participate in roleplaying games like D&D, which gives them the opportunity to practice social skills and develop friendships in a safe environment.

Organizations like these have listened to Sinclair’s call to make this world for people with autism, and to accept that they are here, and deserve to be here. Because as Ralsei says:

“This world is full of all kinds of people, Kris. In the end, how we treat them makes all the difference.”

Megan Pitz is an Asian American writer, JRPG enthusiast, and lover of all things cute. She has published research on the impact of BIPOC representation in children’s literature in Critical Insights: Jamaica Kincaid, and continues to write and research about the impact of BIPOC, queer and neurodivergent representation in youth.