Let’s Talk Accessibility In Games with Sumo Group

Posted: 12 Mar 2024From action-packed racers to narrative-driven adventures, studios across Sumo Group are striving to make gameplay as fun and accessible as possible – with the aim that more people can enjoy some of the best video game titles out there.

We spoke to four people from across Sumo Group’s studios about the importance of accessibility in games and share their top tips on how to implement it.

WHY IS GAMES ACCESSIBILITY SO IMPORTANT TO PLAYERS?

Sumo Sheffield’s Associate Design Director Joe Kinglake has over 12 years of game development experience – having worked on Killzone: Mercenary, HITMAN 2, and Star Citizen, as well as indie puzzle titles. They are currently working on an unannounced game from Sumo Sheffield and recently hosted an internal talk as part of SDCXtra (Sumo’s bite sized learning programme) about accessibility.

“Accessibility is about eliminating obstacles and ensuring equal opportunities for individuals with diverse abilities and needs,” Joe said. “Accessibility is the very definition of democratisation of making video games playable by all. Right now, there are unintentional barriers that we, as an industry, are creating and putting up that prevent everyone from enjoying the experiences we play.

“The phrase ‘Games are for everyone’ sometimes seems like a throwaway statement if not acted upon,” said Ladell Smith, Social & Community Manager at Auroch Digital – who is also a Safe In Our World Ambassador, WiG ambassador and one of Sumo’s Diversity Champions. “

We know that the world is full of diverse gamers and therefore why are we not trying to lower some of the barriers for them so they can still enjoy games?

“There is always learning and more to be done with accessibility and the more highlight it gets, the more improvements we will achieve. The less gatekeeping people will do and also people can feel more comfortable voicing their opinions on what their needs are with more mainstream media bringing up accessibility.

James Schall, Vice President of Publishing Strategy at Secret Mode, added: “We have to embrace the world of gamers as well as people who want to enjoy games, but can’t. That is not just thinking about the same demographics that we used to look at, but also age, neurodiversity, physical ability, vision impairment or audio impairment.

“If we can reach and delight players across these wide groups, we have more potential to succeed.”

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO MAKE GAMES MORE ACCESSIBLE?

“In a recent talk at Sumo, I covered misassumption topics such as ‘Disabled players don’t play games’, ‘This game is too competitive for accessibility to be fair’, and ‘Accessible games are implicitly imbalanced and unfair’,” says Joe. “I believe that perpetuating these misassumptions is a sure-fire way to build an inaccessible game, so my goal was to challenge the misassumptions to show that disabled players do want to, and are already playing multiplayer games but that multiplayer games are putting up barriers for players at a greater rate and underserving players. The conclusion of the talk spoke about tools we can use as developers to tackle accessibility in multiplayer titles, without harming the fairness & vision of your game.

“In summary, it was a talk about how to identify the unnecessary points of inaccessibility through the lens of your vision, core fun and primary challenge of your game. Overall, it’s important to understand that accessibility isn’t about giving players an unfair advantage, it’s about normalising the barriers to entry to your game to make sure everyone can reach the fun.

“We aren’t going to get it perfect, but we have a responsibility as owners of digital spaces to make sure that everyone can access them. Design features that intersect your vision and audience’s needs and let everyone get to the fun.

“Generally speaking, we need to communicate better as an industry around accessibility. Speak to our players early about what our games offer to let everyone get involved in the hype train, test your games for accessibility and listen and react to players’ needs where they are excluded. There’s a fantastic quote from Xbox, which I love to use in all my presentations on accessibility, which is ‘When everybody plays, we all win’.”

From Xbox.com

Joe also discussed Sumo Sheffield’s approach to accessibility in one of its most popular titles to date, the multi-award-winning Sackboy: A Big Adventure.

“We tried to target several features across a range of disabilities to help as many players play as possible,” they said. “We opted for full control customization knowing that players have different needs and wants for customising their experience.

“This included options we specifically considered for players who may have non-standard setups and controllers e.g. stick swapping, separated axis swapping on joysticks, full button remapping, swapping taps versus holds.

“We offered a range of game assists to allow players to adjust the complexity of the controls and game – these included swapping Roll from tap to hold, swapping Grab from hold to toggle, hold to flutter (reduces the need to rapidly tap jump), infinite lives, and gyro control alternatives.

“The Action Almanac is a guide and reminder that details how to use each mechanic and movement feature in the game. Complex controls can sometimes be difficult to recall for any player but especially for those with impaired memory. It’s also benefited players returning after a long time away, players who didn’t initially understand the tutorials, and players who simply wanted to better understand the game.

“We had a strong creative vision for the game, but we didn’t want this to come at the cost of players being able to participate and enjoy the game. So, we included an infinite lives toggle that lets players adjust the challenge of the game.

“Knowing that vibration can be critical for communicating gameplay information, but also provide a barrier to some players – we opted to allow players to fully scale the amount of vibration in the game rather than simply offering a toggle.

“Since we know no two players are the same, and playing together with other players can often cause barriers – we devised the ‘Assistance Copter’, pull out a flare, call for a helicopter to come and pick you up and it’ll whizz you off to the lead player, bringing you back together.”

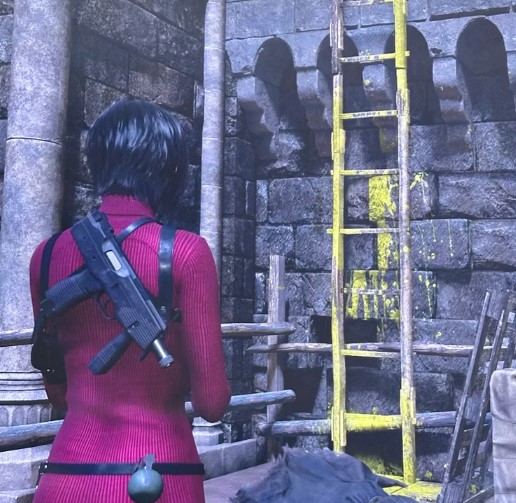

“One example that has recently been floating around the internet is the ‘yellow ladder’ in Resident Evil 4. Let me tell you about how amazing that is even though most of the Twitter [X] community thinks that it’s a joke” says Smith.

“Firstly, Resident Evil is such an immersive game that sometimes you are not sure what you can and can’t interact with, so having it highlighted in an opposing colour is key of a lot of players with accessibility needs.

“I am one of those. If the barrels and ladders aren’t indicated, I tend to get distracted or not notice them. It is a cognitive issue that happens in multiple games and having clear cut indicators helps.”

Jacek Szydłowski, Senior Software Engineer at PixelAnt Games, has also previously delivered a talk on accessibility, sharing four key focal points to make your games more accessible to players.

“Step one is to plan for accessibility,” said Jacek. “To have a good plan is building knowledge among your team, that the game needs to be accessible. It’s not something that can be added on at the end of the project; this is a fundamental part of the game, like visuals, audio, or gameplay.

“If you plan it from the beginning, people will make good choices. When the concept artists draw something, they know that they need to think about colours being visible properly and about contrast.

“Basically, be sure that your team knows that this is a fundamental part of the game. Accessibility needs to be the foundation of the game, as it’s way easier if you work on it from the beginning.

“Step two, give players a choice. Have all the necessary accessibility features in one place so the user will know where to find it. What’s more, the user should be able to preview what each setting does.

“If you have subtitles in the game, the user should be able to change the font size – e.g allowing players to change the default font to the free font called OpenDyslexic, a font designed to be easy to read for people with dyslexia, or Comic Sans – one of the best fonts for dyslexic people.

“Audio descriptions allows someone that cannot hear, to not only see what people are saying, but also to read about the explosions, gun shots etc.

“In competitive games, if someone is not able to communicate via voice or is not able to listen, you can provide the option to quickly communicate with other players via in-game quick chats, without the use of a microphone at all.

“Input remapping is very important as both current generation consoles have the possibility to globally remap the controls, but it’s the last resort. You should have that possibility implemented in your game, since not every player is able to play on the keyboard or on the controller in the same way.

“Another thing that you could add as an option is something that, for example, is an assist mode. If the game is too hard for someone or they are not able to physically do some things in this game, you can for example change the game speed.

“Step three, playtest your game. By playing our game, we will not only find bugs and other problems, but also barriers. This is the most important topic with regards to accessibility: if you don’t find barriers, your players will.

“Step four, ask and listen. Even if you ensure all the above steps, you might still miss something. Asking for feedback and listening to people talking about the game are the easiest ways to learn what you can change.

“For example, Bethesda added the ability to change the colours in Deathloop only after the release. It’s never too late to make your game better – Quake, also released by Bethesda, was updated 26 years after the release; just a while ago they added accessibility features.”

“It’s difficult as there are so many key parts to this,” says Ladell. “But I would break it down into three parts. First are the controller settings – do you let multiple controllers play you game and are your keys re-bindable? These are massive in terms of accessibility for players to be able to gain access to the game. I believe all games should have re-bindable keys, but I also know it is not always possible.

Secondly, do you have colourblind mode? How are you appealing to players who have vision impairment? This can go down a whole range of ways in which we can lower the barriers for players with vision issues but if you can at least include colourblind mode, that is a great start.

And thirdly, what languages are you offering, and do you also do the captions/text in those spoken languages?”

To summarise, Schall says…

“There are two strategies: one is to use the excellent resources made available by SpecialEffect. There is a ton of information and good work in place there to advise and guide.

“Secondly, think about what barriers could stop someone playing your game: vision, sound, neurodiversity, complexity, triggers, difficulty, dexterity of controller operation and many more. Then try and offer solutions that remove the barriers or offer solutions for players to enjoy the experience you are creating.”

There’s still a long way to go to make games more accessible to players but taking one small step at a time up that yellow ladder, Sumo and many other developers in the industry are making the necessary steps to a better, more practical future for all gamers.

Written by Sam Hamilton-Jones, PR & Communications Manager.