How Red Dead Online helped me talk to my brother about mental health

Posted: 19 Apr 2023“It’s a nasty world out there, and it’s catching up with us…”

It’s 2001 and a much cuter and happier me is wandering wide-eyed through a tire-trodden rugby pitch at a local car boot sale. Car boot sales are something of a dying British pastime and a veritable treasure trove of useless tat; a pop-up wooden table selling stolen cable and dusty crates full of decorative plates gives you an idea of the sort of fare on offer – and I’m sure I’m not the only person with good memories of trundling along as a kid, a 50p coin burning a hole in your pocket.

The weather is always crap and it shows on everyone’s faces – but for me and my brother this cold and grey morning was the beginning of a great weekend. Times were often tough for my family – they raised us well and they gave me more than any toy or game ever would – but things didn’t come easy. It was rare that we would get a new game on release – from my memory the only times this would happen would be for Grand Theft Auto or Metal Gear Solid, so car boot sales presented the perfect opportunity for my parents to grab something cheap for us to play. Among the cars, there would be a few people selling demo discs (the ones that came packaged with the PlayStation magazine) for 10 or 20 pence each, and with only a £1 coin in hand we would return home with 5 or 6 of these for the coming weekend. This was by no means an enjoyable way to play videogames and it makes me laugh to think about how we would have to reset the console every time we wanted to replay the first 10 minutes of Silent Hill 2. My patience for games has certainly dwindled since, but as a child you find entertainment in the strangest of things so we would always have a blast. The hours spent playing the first level of Time Crisis 2 on repeat or messing around for 30 minutes in Bugs Bunny & Taz: Time Busters are some of the fondest I have with my brother, and playing co-op games has been an integral part of our relationship since.

Fast-forward 20 years, the two of us have some war wounds – deep bouts of wavering depression, addiction, and anxiety had affected me during my time at university, and my brother was suddenly grappling with what we now know is schizophrenia, that meant a brief stint in the hospital. During this time he had to take leave from his degree and move back home. It was a difficult time for all of us and as my family moved to a remote group of islands some time ago it had always been a challenge organising a trip home whilst also studying and working.

Aside from a handful of visits to the hospital that I was able to travel for, I was feeling rather helpless – my other commitments meant I couldn’t stay home for an extended period of time to help ease the load and I so desperately wanted to do all I could to help my brother get better.

It was around this time that A Way Out had released – me and my brother had followed this game intensely since the original announcement revealed it was a split-screen only game and we made a determined effort to play it together despite the circumstances.

Working through that story reminded us how much we loved playing games together, and even though we were hundreds of miles away from each other, it almost felt like he was sitting there beside me as we shimmied carefully up the prison air ducts. Playing A Way Out was just so much fun that we would forget about all our anxieties and woes at a time when my brother found it difficult to trust people.

There was something cathartic about going back to that space where we could have fun like we did as kids, and the design of A Way Out felt purpose-built for capturing that nostalgia. After this, I think we subconsciously made an effort to try and play games together more often – we had enjoyed it so much and it helped us reconnect and feel closer.

As time passed, my brother’s health had improved – there was still a long road ahead of us but the future looked bright when at times it had been tough to stay positive. Although it ultimately brought our family closer together I think a lot of things pertaining to our mental health had been put on hold when my brother took ill and this is something that we haven’t fully worked out as a family how to talk about yet. For me and my brother, the last two years began to repair what had at times been a tested relationship, and although we had yet to openly discuss our health we felt comfortable talking and the darker times that had prefaced this felt increasingly abstract as days went by.

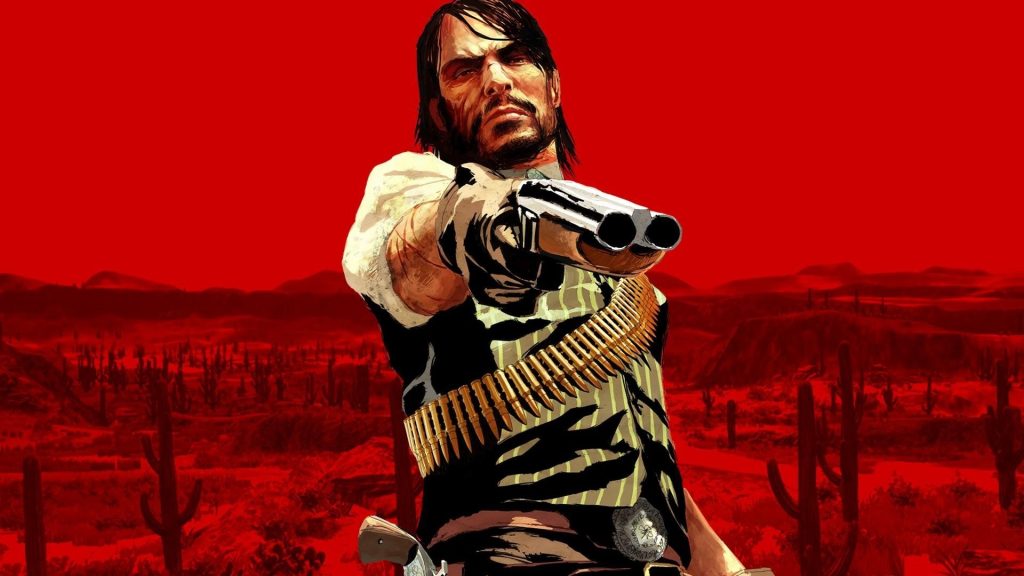

Gaming was still a huge part of our lives and as large swathes of the community were also doing at the time, we were tempering our unrequited excitement for Red Dead Redemption 2. The Red Dead series had made a big impression on us way back when Revolver came out and the childhood fantasy of gun-slinging in the Wild West with your buddies is one that I imagine most adults still spend inordinate periods of time daydreaming about. Red Dead Redemption had given us a taste of what this online world of outlaws could be like and 2 was another step closer to the Westworld we secretly hoped existed.

As fans of cooperative narrative experiences we jumped straight into the online campaign – although short-lived and relatively lacklustre, we both reveled in the opportunity to pull up our boots, polish our stirrups and get back in the saddle again as guns-for-hire for Jessica LeClerk. After a few hours of stranger missions, delivery tasks and general trouble-making we found that the expansive world that Rockstar had pulled from the single player story was severely lacking in content once you complete the initial short story missions.

Recurrent player challenges that offered little in the way of creativity, empty towns and saloons, abusive players and a general lack of interactivity hampered what should have been an engaging, multi-faceted and breathing open-world. The small details are what make Rockstar’s worlds so believable and immersive, and in the case of Red Dead, these were the innocuous and amusing activities made available to the player. When me and my brother had our fill of riding around shooting and lassoing one another we would often spend our time moseying through the world hunting, riding, playing poker, but most importantly – fishing.

A quick trip to Valentine to sell five or six sock-eye salmon would often turn into a three-hour stint as we tried to force a crashed station wagon with one horse up a steep mountain as fish are flung mercilessly out of the back – think more Blazing Saddles than The Hateful Eight.

This laid-back way of playing with no pressure to complete missions or time-sensitive challenges meant that we could play at our own pace, and as we often used games as an opportunity to catch-up this presented the perfect opportunity to take things slow and simply enjoy one another’s company. A lack of player interaction or storytelling gave us ample time to talk, to laugh and to enjoy ourselves at a difficult time and I think the virtual environment certainly tempered our anxieties. It felt easier to talk round a fire as we cooked our latest catch than to speak through the phone or message.

Neither of us are particularly interested in role-playing in online games, but something about the world around us – the natural landscapes, the whistling of the wind, complete isolation from the civilised world – had us both completely immersed. Hours would pass as the two of us would ferry our catch from town to town, a time-consuming effort broken only by conversation. The slow pacing and nuanced style of Red Dead 2’s game design meant that long journeys were common, and in the days of the Old West they had nothing but each other’s company to pass the time. I would tell him about my day and the issues I was having, and in turn felt more comfortable asking him about his problems. When before it had been difficult to speak to my brother about his health, here we could discuss it more openly.

Even though we were escaping from the real world – the lack of anxieties and pressure afforded by the virtual world meant we had breathing space to talk more freely about real-life problems. A Way Out had given us a driven experience and thrill-ride that helped us bond in the same way the two titular characters did. Red Dead Online handed us a freely open world, a horse, a gun and a fishing rod, and the blank canvas we needed to build our own story – two brothers rebuilding their friendship (and who also fish from time to time).

A thick fog rolls over the lake where me and my brother stand rod in hand, two happy lures bobbing satisfyingly on the surface of the water. The stretching shadows of nearby mountaintops mark the passage of time, the occasional sniffle of one of our horses or the echo-carried roar of a distant brown bear are the only sounds that break the serene quietude of our chosen fishing location. As I look out into the water I see my brother standing there, ripples protruding from where his knees touch the lake’s surface. I think back to our childhood and how much simpler things used to be.

Games were a fun way for us to do something together as children, and as years have passed the way we interact with those games has changed. We may not be able to sit next to each other, twisted controller cables strewn across the living room – but we can play the same game, hundreds of miles away in an immersive world set years in the past. When times of adversity hit us hard, it was that same childhood love for games that helped us rebuild a tested relationship, learn to trust one another again, and talk openly about our troubles.

In a modern world wherein technology can play a damning role in our health and wellbeing – it is easy to forget that it has innumerable applications for making positive change in people’s lives. Greater inter-connectivity presents countless opportunities for allowing us to communicate with, care for, and have fun with the people we love. Games can be a wonderful form of escapism in times of hardship, but they can also be a bridge for connecting people – a place where we can meditate on, express ourselves, and then begin to make sense of difficult situations in our lives. My patience for games may have diminished since the days of car boot sales, but my patience for listening to others has grown – and I have my brother, and our love of videogames to thank for that.

by Brandon Cole