Blinnk and the Vacuum of Space: An Interview with Changing Day

Posted: 22 Sep 2022We spoke to Alison Lang, CEO of Changingday to talk about their new title ‘BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space’, which is made by and for autistic people.

Tell us about the origins of BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space; what’s the game about? Who is the target audience?

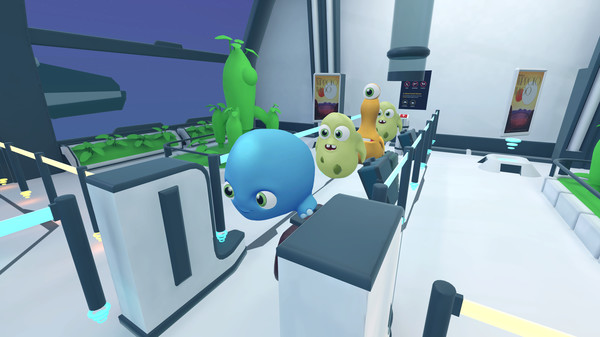

The game has evolved a lot over the last five and a half years, but the original idea was for a VR game that autistic people would want to play because it was fun, but which incorporated real life scenarios designed to help the player cope with everyday life. The game has grown, so that it’s now set on a space station full of aliens and robots, but the core idea is the same.

The game is divided into levels which the player will recognise, like a park, a dentist, or a spaceport. The player has to travel to each to recapture escaped alien creatures called groobs with their trusty Vacuumiser 5000. Along the way, they complete various tasks which are designed to challenge and support them.

The target audience is primarily autistic people 13+, and also parents or anyone who knows an autistic person who might enjoy gaming.

BLINNK has been designed to harness the power of VR to give autistic people greater confidence while enjoying a game designed for them…

What was the inspiration behind this?

Autistic people play more video games that neuro-typical people, and they particularly enjoy VR. We did a lot of research which suggested that some deficits autistic people experienced in real life disappeared in the virtual world, and that the confidence that they gained in the virtual world would remain after they had finished playing the game.

Why use VR as the medium rather than a non VR game?

The immersive nature of VR transports the player to a world where they are in control and which lets them go at their own pace. In this virtual world, they can be themselves and play on their own terms, without worrying or stressing about what’s going on around them. For the autistic player, this escape gives them freedom and reassurance to relax and enjoy themselves.

Tell us about the range of accessibility features that you’ve implemented within this game and their importance.

Autistic people are not easily pigeon-holed. They as varied and unique as any group of people.

There are characteristics and behaviours which many of them will share, but a one-size-fits-all approach is impossible to achieve. In developing the game, we have incorporated multiple features and elements designed to make it easier for the autistic player to play and enjoy.

Beyond that, the experience can be fine-tuned further through a detailed accessibility menu to adjust a wide range of sensory inputs, from colour, to volume, to haptic feedback. They can turn down, or even switch off sounds that they find particularly intrusive. Allowing them to individualise the experience according to their own sensitivities.

As your first game, what have been your biggest challenges in the development process?

It hasn’t been easy to develop a game that will appeal to as many autistic people as possible.

As parents, we have had a lifetime’s experience of autism. We felt it was vital to build on our understanding through an extensive programme of research. This also ensured our team understood our audience and the challenge of what we were trying to do.

This has informed every decision we’ve made to try to make the game as enjoyable and beneficial as possible.

Perhaps the biggest challenge, however, is accepting that we won’t get everything right. We have to learn from the reactions of our audience to this first game, so that we can make the next game even better.

What’s one thing you’d encourage other developers to consider in the earlier stages of developing a game?

To think less about the game and more about the person who will be playing it.

As gaming, and VR in particular, broadens its appeal to a wider audience, accessibility is going to be more and more important. Not just the obvious things like text size, or volume control, but in the design and implementation of the gameplay itself.

Is it possible to complete a level if the player gets stuck at one point? Does the way a character acts make sense beyond the game, or is it just because the game demands it? If a player has a particular sensitivity, does that mean they cannot play the game?

These are all important considerations which can tempt or put off not just autistic people, but all potential players. We hope that BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space provides a good example.

For more information, contact:

Alison Lang – CEO, Changingday

alison@changingday.com