My long and winding road to successful therapy – and the huge role video games played along the way

Posted: 30 Sep 2024You’re allowed to be angry, said the counsellor. And it’s a sentence that changed my life.

I’m far from a Pollyanna type. I definitely err on the side of pessimism by default, and I’ve often wondered if there’s a glass on the table at all, far less one that may be half empty or full.

Over 16 years ago, I lost a loved one to suicide and I’ve struggled with my mental health ever since. I’ve written about the depression and anxiety disorder I was thereafter diagnosed with on many occasions since – not least here on the Safe In Our World website – and have also waxed lyrical about how video games have provided a constant comfort and means of escapism and coping during my darkest days.

Games such as Will O’Neill’s Actual Sunlight and Matt Gilgenbach’s Neverending Nightmares were among the first to push me towards counselling in 2014. Aged 28 at the time, I valued the experience, but there was no doubt in my mind that being prescribed medication in tandem with talking to a professional was the driving force in helping to stabilise my feelings.

As such, I dropped out of my first round of sessions after just three visits. My counsellor was nice, but we just didn’t click on the level required to explore the deeply personal, raw and sensitive emotions that I’d spent several years burying deep inside with the help of alcohol, recreational drugs and the unreasonably outmoded machismo disposition of working class millennial men.

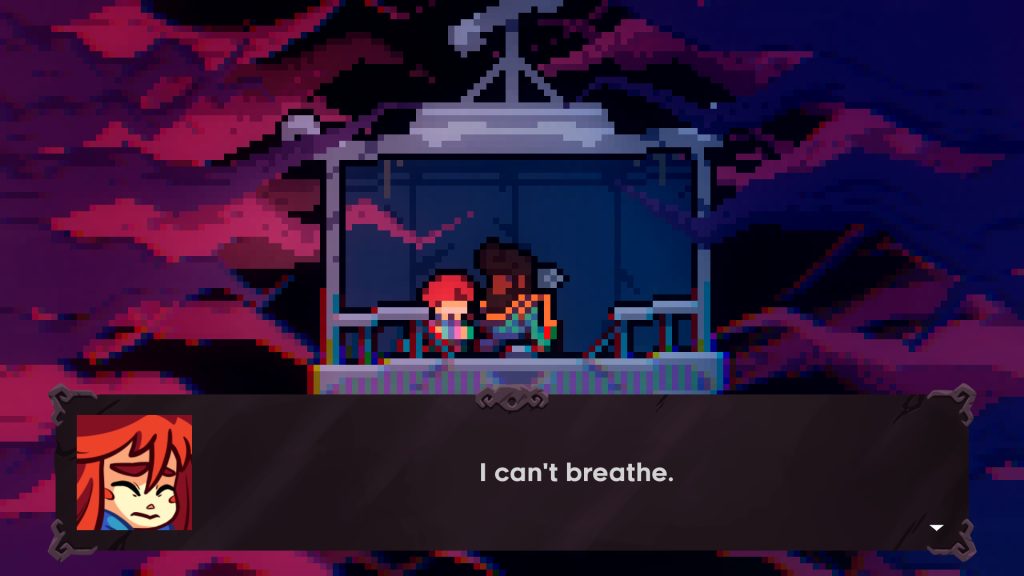

I tried counselling again in 2018, inspired by the likes of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, Celeste and Night in the Woods – but again it didn’t stick.

I began thinking that counselling, perhaps, just wasn’t for me; that I could be grateful knowing I’d found balance in medication, my support network, and the relatable and enlightening tales that my favourite video games could provide.

Naturally, I’d always championed the virtues of therapy to anyone who’d listen. I’d spoken to so many people over the years who had made significant in-roads into healing themselves, learning themselves and bettering themselves by opening up and putting it all out there and being vulnerable. And even although I’d struggled to reach these epiphanic moments myself, the myriad real-people case studies that’d crossed my path over time were tangible proof the process works.

But, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t jealous of them. Depression is a selfish affliction, and while I am genuinely delighted whenever I hear of someone doing well, it is often framed by my own circumstances at that moment. That’s not an easy thing to admit, but I’m fairly certain anyone who’s been diagnosed with depression and/or anxiety disorder will be familiar with the ubiquitous mirror-holding that goes hand-in-hand with the condition.

I’m so happy you’re feeling well, I really am. But why don’t I feel the same way?

In 2023 I gave counselling another try. I’d been replaying the masterpiece that is What Remains of Edith Finch, and had been swept off my feet by its expert narrative and tone-perfect execution. Reacquainting myself with the titular character’s ill-fated family members, their plight and their poignant stories moved me more than ever before, ultimately leading me to reconsider my position regarding sharing my own experiences. What Remains of Edith Finch isn’t exactly what you’d call a mental health video game per se, but by putting the dysfunctionalities of family life under the microscope – albeit a super-duper eccentric one, in this instance – some easily relatable, universal tenets come to the fore, each of which spoke to me louder than I remembered the first time round.

I signed up for a third bout of counselling through the NHS shortly afterwards, this time at a different health centre with a different therapist. After outlining my story so far during our first meeting, including the brutal nature of my loved one’s passing and the long-term issues I’ve dealt with ever since, my counsellor told me it was natural to still have residual, unprocessed feelings given the circumstances that’d led me to this point.

“You’re allowed to be angry,” said the counsellor.

And it’s a sentence that changed my life.

It was so simple, and yet it blew my mind. Again, I could never claim to be a beacon of positivity day-to-day, probably less so the older I get, but in the same breath I’d never considered being angry with the nature of my loved one’s passing, or how it made me feel or how it’s made me feel for the majority of my adult life. I was 22 when they passed, and I’m 38 now. I’m no longer angry, but by simply being told it was okay to feel that way was like flicking a switch in my head.

Suddenly, therapy worked for me. It was the simple breakthrough I needed, and helped me surface the most affecting residual feelings I’d been unwittingly holding onto for the longest time. By being given permission to feel a certain way, or, at the very least, by having it vocalised for me, I was able to resolve so many thoughts in my head and finally get something from talking to a professional. I may have made this discovery on my own in time, but in this instance it was 100 percent made possible by revisiting Giant Sparrow’s 2017 first-person exploration masterpiece.

Through all of this, I suppose the moral of the story is to acknowledge how difficult seeking professional help for depression can be. I first formally acknowledged that I was depressed around 2011 after years of being in a dark place. It took me a year to speak to my GP in 2012, and another two years after that to first see a counsellor in 2014. I tried to make therapy work twice between 2014 and 2018 and finally had my breakthrough in 2023.

Seeking professional help is not an easy thing to do, and speaking from experience, it’s even harder to return when you’re unsure if an outcome even exists. The ol’ glass half-full / glass half-empty / glass lying on the floor smashed into a thousand pieces conundrum. I’m living proof that no matter where you stand on that one, there’s something in it for you whenever you’re able to make that first step.

Joe Donnelly

Joe Donnelly is a Glaswegian writer, video games enthusiast and mental health advocate. He has written about both subjects for The Guardian, VICE, his narrative non-fiction book Checkpoint, and believes the interactive nature of games makes them uniquely placed to educate and inform.